"I think the general public, through no fault of their own, drives over a bridge and never looks down. We're trying to change that."

- Dawn Buehler, Kansas Riverkeeper

Do we stop to think how important rivers are for wildlife, agriculture, recreation and for being the reason humans formed a civilization in certain areas?

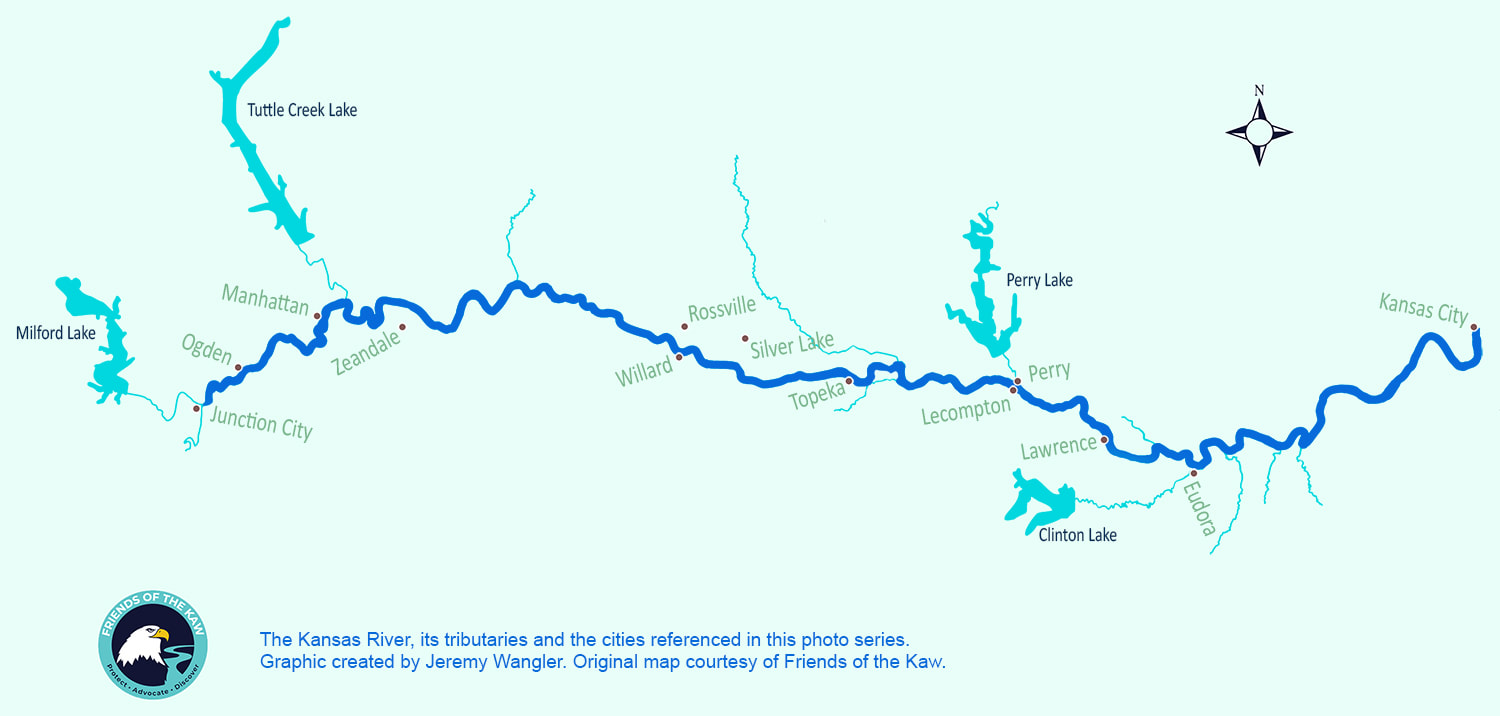

"Confluential" is a look at the Kansas River and the influence it has on life in northeast Kansas.

"Confluential" is a look at the Kansas River and the influence it has on life in northeast Kansas.

Why did I chose the Kansas River? It passes three blocks from my home and provides drinking water for 800,000 of my fellow Kansans.

As you view these photos and read these words below, I hope you think about how critical rivers are in your environment and how critical we are to the rivers.

As you view these photos and read these words below, I hope you think about how critical rivers are in your environment and how critical we are to the rivers.